Skywalker

Act Two: “Zemeckis, Levinson, Lucas, Spielberg, Hanks, Williams, Goldberg, and… Skrovan?”

George Lucas was used to making commercial hits, and although he was under no illusion that a movie about education in the year 2025 would be a blockbuster, he wanted to give it as much commercial appeal as possible so that people would want to at least check it out. He told me he was going to direct one piece. He was going to get Robert Zemeckis (Back to The Future; Forrest Gump) to direct another piece; Barry Levinson (Diner; Rain Man; Good Morning Vietnam) a third; and none other than Steven Spielberg (do I really need to give his credits?) to direct the fourth. He’d get Tom Hanks to play the dad, Whoopie Goldberg to play a teacher, and Robin Williams to play another part yet to be determined. Wow. I guess if anybody had the power to make that happen, it would be George Lucas. One day when I was waiting to be admitted to the office, I noticed a phone in the hallway that had those directors written on tabs next to speed-dial buttons. I was just wondering what the hell I was doing in that line-up: Zemeckis, Levinson, Lucas, Spielberg, Hanks, Williams, Goldberg, and… Skrovan. One of these names doesn’t belong.

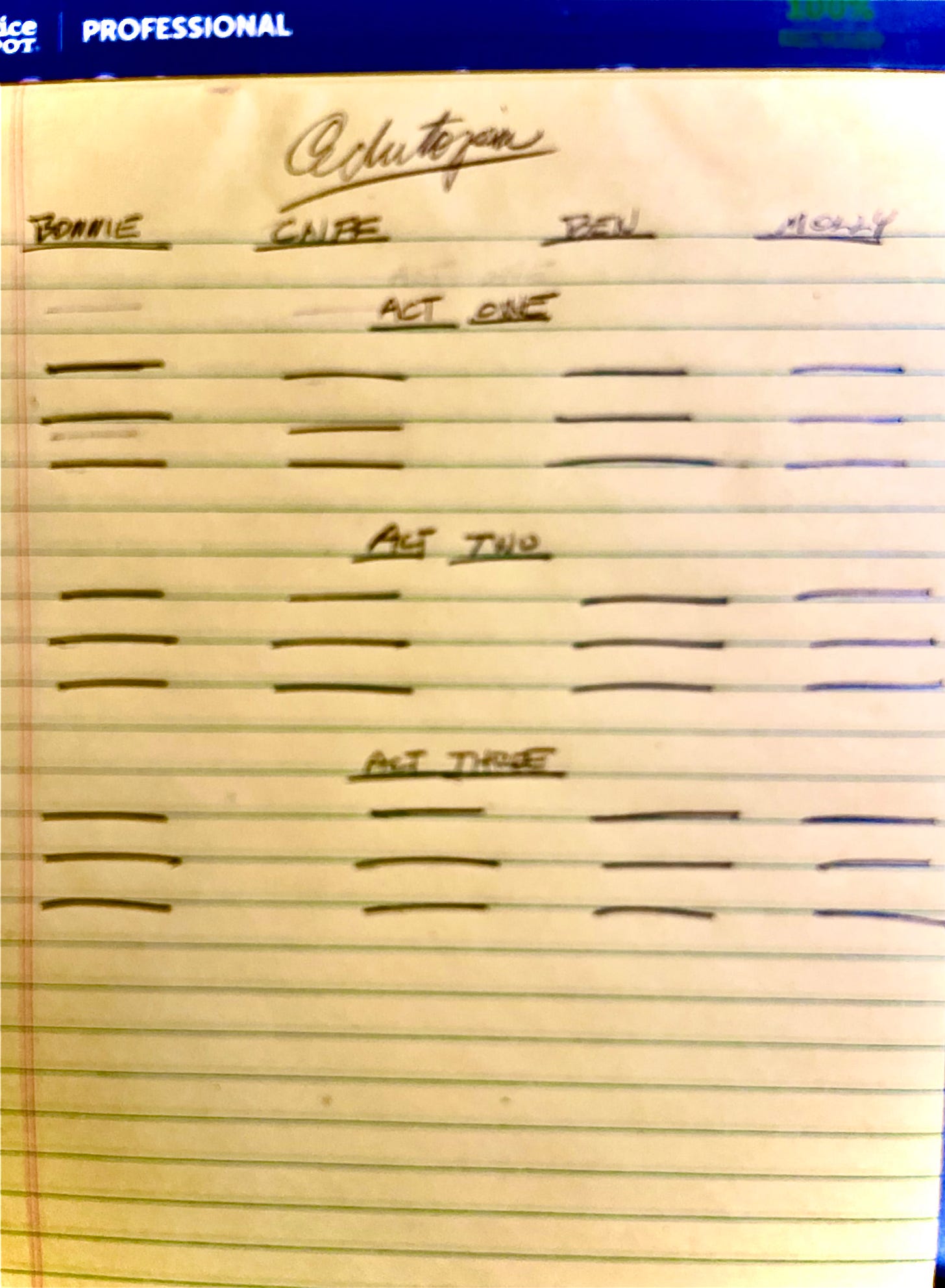

At the top of his legal pad, George wrote the names of the four main characters: a teacher named Bonnie and three kids from what we were calling the Newell family, two boys and a girl. Cliff was in high school, Ben middle school, and Molly elementary. Then he made three hashmarks underneath each name. Then he made a space and drew three more hash marks below those, then another space with another three hashmarks beneath those. He explained this is how he worked out the outline for American Graffiti, which was his first hit, a story that harkened to his teenage days cruising the streets of Modesto, California. That script weaved four small stories together.

The first set of three hash marks represented Act One, the second Act Two, and the third Act Three. Each Act had three beats.

We thought of an action described in a short phrase or a couple of words and filled in the lines, so maybe for the third beat of Act Three under Molly, we’d write “makes presentation” or under Ben the second beat in Act Two would read “meets mentor.” It wasn’t necessarily sequential. We might know the third beat before we knew the first beat or the second beat before we figured out either of the other two. The rough outline would be finished when all thirty-six lines were filled in.

We agreed that none of the plots in the reworked story were going to be high-stakes life and death matters. The idea was to create just enough conflict and place enough obstacles in the way of our characters to give a modicum of dramatic tension to each small story of a teacher and three students, each at a different stage of their schooling.

As a young writer, I found this to be a valuable lesson in how to organize a complex project. This particular technique was akin to piecing together a quilt or mosaic. It worked for this story, which had many moving parts that needed to be woven together. Not every project can be outlined in this fashion. Each story has its own unique characteristics. But depending on the nature of the story, finding different ways to break something large and potentially overwhelming into small, manageable pieces was a formative takeaway for me.

Every screenplay runs on two tracks. The main track is the plot plot: the action, the mission, the journey, the dream the characters are pursuing. The second track is personal to the characters, usually a relationship plot, an emotional passage, or plot elements driven by personality quirks.

The problem with the first script was that it only dramatized the main track. There was nothing else going on in the characters’ lives other than their schoolwork. As a result, the characters didn’t seem real. They lacked dimension. Over the years, I have learned that the two tracks should be constantly crisscrossing, always getting in the way of one another. The main track interrupts the personal track and vice versa. I always ask myself before I write a scene, “What life is going on that the plot is interrupting?” Or “How is the personal track changing the course of the main track?” A spy is on a mission and falls in love with the person they’re spying on. Someone is walking their dog and witnesses a carjacking. That type of thing. Or in a less melodramatic story, it could be someone folding laundry when a package lands at the door.

Janice sat in on our sessions along with Steve Arnold, a board member and cofounder of The George Lucas Educational Foundation (GLEF), a pleasant, good-natured presence, who chimed in every so often but basically let us do our work.

We decided that the main plot for each kid would be a particular school project. The high school son, Cliff, is doing a simulated space shuttle landing. He’s concerned about getting into college. Ben, the middle-schooler, is working on a virtual archeological dig. Personally, he is distracted by a girl in his class, whom he wants to ask to the Eighth-Grade mixer, but he can’t seem to work up the courage. Molly, the second grader, is working on report about a sloth with another student, who lives in Costa Rica. She has to make a presentation in front of the whole class in two days but is experiencing some performance anxiety. We tied Bonnie to our family by making her an academic advisor for Cliff.

After a lunch break, George and I walked up the stairs to his office and I, trying to be clever, said “Maybe instead of going to all this trouble, we could just repackage a Mad Max movie and tell people this is the consequence of not paying enough attention to education.” I meant it as a joke, but George took it seriously. “No,” he said. “You have to give people a positive vision to head toward. If you give them a negative vision, they will head toward that.”

The longer I live, the more I realize how right he was.

By the third day, I was comfortable enough to disagree with George on a story point. Without getting too far into the weeds, it had to do with whether a thirteen-year-old girl would be mature enough to change her mind about going to the dance with our thirteen-year-old boy if he changed his behavior in class. We had a long back and forth about it.[1] Janice and Steve Arnold not surprisingly weighed in on George’s side. Despite that, I held my ground for quite a while, and he patiently dealt with every point I made, never once suggesting, “Hey, do you have any idea who I am, you little shit? I am George-fucking-Lucas! I think I might know a bit more about storytelling than a shitty night club comic who spent one year on a fucking sitcom before getting his ass shit-canned! You feel me, motherfucker?!”[2] He had every right to say something like that. Yet he did nothing of the kind, just calmly indulged my objections and explained his view of things. I have found that the most talented people I have worked for over the years, namely Phil Rosenthal, Larry David, and Jay Kogen had the same quality George exhibited in this instance, a high tolerance for dissent. That’s a leader with confidence, someone who knows what they’re about but is not threatened when they are questioned and is willing to entertain the possibility that they could be wrong.

The most “space-age” thing on the ranch was the house I spent the nights in, a large, well-appointed two-story guest house on the Skywalker grounds that was completely round. No right angles. Don’t ask me why. It was probably just something cool to build. I have since tried to find a picture of this building online or even a reference to it in articles about Skywalker Ranch. I can’t find anything. Maybe I’m just bad at the internet. Or I was hallucinating.

Before I left, Janice pointed out a back window of the mansion to a small complex of modern office buildings. Those offices were filled with lawyers, she said, who handled all the ancillary marketing of George’s various projects and helped protect him from lawsuits. Because George’s empire was so vast and affluent, he was a frequent target of lawsuits. They had to be extremely careful about what they put out into the world. She told me that everything had to be carefully vetted, for instance, if there was blackboard in the background of a scene with a mathematical formula on it, they had to make sure that formula didn’t originate with anyone else who could sue them for stealing it.

At the end of the sessions, George shook my hand and wished me luck. I told him what an honor it was to work with him and said, “Hey, next time, you come to my place.” He stared at me for a moment, uncomprehending. Then he nodded and grunted, all he could muster for that skimpy attempt at jocularity. His mind was probably already onto something else, quite possibly the bane of having to turn his attention back to the dreaded Star Wars prequel.

I, on the other hand, excitedly went off to write a script for Tom Hanks, Whoopie Goldberg, Robin Williams, Robert Zemeckis, Barry Levinson, George Lucas, and Steven Spielberg.

End of Act Two

Tomorrow! The Exciting Conclusion!

“The Skro Zone”

[1] Janice graciously granted my request for the cassette tape of that particular session, and listening to it for the first time thirty years later, it’s civil, but we’re talking over each other like people do in these kinds of debates and I can’t help saying to my younger self, “Shut up!’

[2] A little creative license: I don’t believe the phrase “you feel me” had entered the lexicon by 1995.

Your wonderful story reinforces what I had gleaned from Lucas's films: not a funny guy. I loved your parting joke!

Love the insight into one writing technique