Skywalker

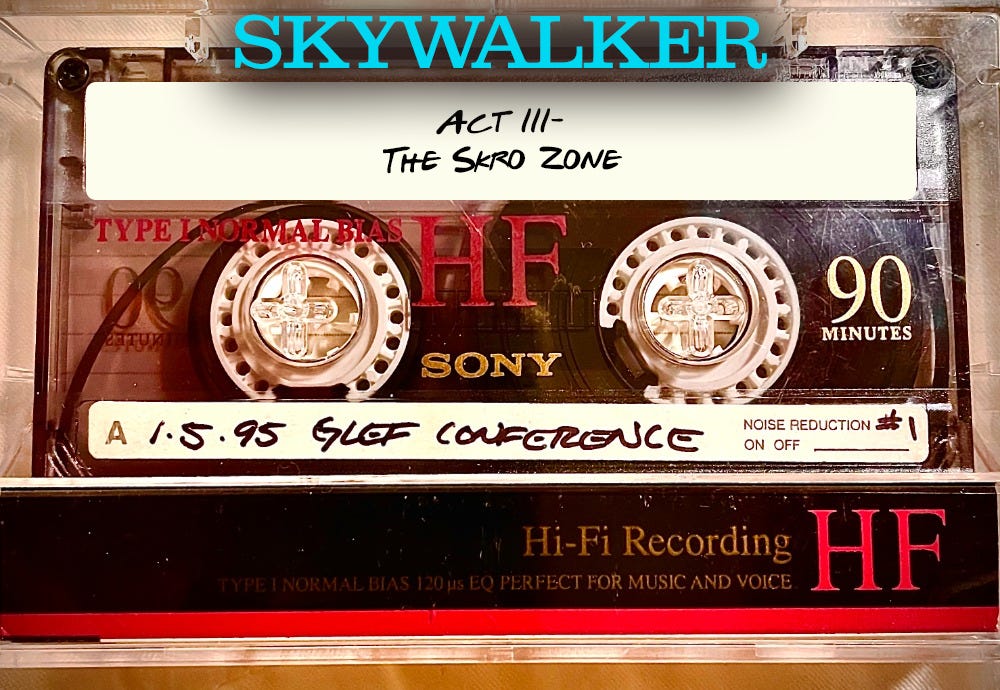

Act Three: "The Skro Zone"

I flew back home to my ranch. And by that, I mean the ranch-style house in Southern California we were renting. A simple rectangle. All right angles. No complex of offices filled with lawyers in the back, just a plastic playhouse on the concrete patio notched together in the shape of a log cabin. I had no office, just a desktop word processor set in a nook in the hallway that used to be a closet until Shelley took the doors off and loaded it with shelves. So long, Skywalker…

Welcome to… The Skro Zone.

From the gift shop at Skywalker, I had brought back a couple of small spaceship replicas for my son, Sam, who was six years old and knew nothing of the Star Wars franchise. I had also secured a VHS tape of the first Star Wars movie. I’m not sure if this is true, but I heard that Francis Coppola once told George Lucas that as rich as he was, if he really wanted to make a lot a lot of money, he should start a religion. For so many, Star Wars is a religion with all of its hallowed iconography and quasi-religious references to “The Force” with the attendant blessing “May The Force be with you.” In retrospect, bringing home this swag looked like I had come back from a Northern California spiritual retreat intent on indoctrinating my impressionable son in the Gospel of Lucas. But, instead of a souvenir statue of The Madonna and a crucified Jesus on the cross, it was a model of the Millenium Falcon and an X-wing fighter.

Janice hooked me up with a couple of public schools in Southern California that were implementing some of the technology and techniques that the George Lucas Educational Foundation was promoting. It helped me picture the physical environment our fictional characters would inhabit. I also heard a good story a high school teacher told me about one of his students. The teacher noticed in his science class that this one boy spent all his time using his mechanical pencils to draw skulls. That’s it. He did no other work. He just drew skulls. This teacher was insightful enough to know something was up. He found out that the student’s father had recently divorced his mother and gone home to Japan. The kid was bereft and somehow felt responsible for his dad’s leaving the family. These dark feelings manifested in his drawings of these death’s heads.

In a lot of schools, this intransigence might have simply led to the principal’s office, or to the school psychologist, or at the very least to a failing grade. Instead, the teacher said to him, “These are good skulls. You wanna know how to draw ’em better?” The teacher introduced him to a doctor friend, who was able to show him more detailed renderings of skulls, what the various parts were named. and how it all worked together. Over time, the kid came out of his funk and became the teacher’s classroom assistant. This resourceful teacher had turned a potential disciplinary moment into a teachable one.

As soon as I heard that story, I knew it was going into the script under “Bonnie.”

They had given me a few months to write the first draft and by spring I turned it in. I almost immediately heard from Janice. She wanted me to come back up to Skywalker on the first available weekend to discuss the script. I sensed something was wrong.

This time, there was no rainbow hovering over the Bay Bridge.

Because it was a Saturday, things were pretty quiet around the ranch, and we had the mansion to ourselves. Before we started going over the script, Janice and her associate, another former teacher and administrator named Rosemary, led me back into the THX room. Since I’d last seen her, Janice had obviously mastered the remote and began screening a video for me. I was a bit puzzled, because the video covered many of the points about the future of education they had schooled me on before. After about forty-five minutes, I interrupted the presentation and said, “I know all this stuff. Why don’t we just go over the script?” They were showing me the video because the script left them with the impression that I didn’t know this stuff and I didn’t get what they were trying to do. We retired to an upstairs office and began on page one.

The first scene depicts a typical day in the life of the dad getting the kids, Cliff, Ben, and Molly off to school. It begins with a puppy licking the dad’s face to wake him up and then a cascade of batter splashing onto a hot sizzling griddle, followed by images of maple syrup flowing and butter melting as dad cooks up breakfast. Already, Janice was not a fan.

“Can’t they be eating something healthier?”

The implication being that in 2025 families will no longer eat pancakes. That’s a future I for one want no part of. I may have made a joke along those lines or said something about how Edgar Allan Poe predicted this with his seminal work “The Fall of the International House of Pancakes.” I told them that it just seemed like a relatable, not to mention delicious, way to set up the family; but sure, that’s easy enough to change.

This note turned out to be indicative of most of the other more substantive notes. For instance, the idea that the young seven-year-old girl, Molly, would have performance anxiety ahead of her presentation went against everything they were trying to encourage. Janice said, “The whole point is that these kids would have been doing these kinds of things all the time, and it would be no problem for them. This is what we’re trying to get across.” I argued that if there’s no problem, there’s no drama. It’s not like this was even a big melodramatic problem, either. It was a little speed bump. She would overcome her stage fright and make a great presentation.

We went page by page through the script, and every objection they pointed to was something they felt detracted from the educational message. In other words, anything that made these characters interesting human beings.

In one instance, I needed a scene where the middle-school boy gets to follow a mentor - in this case an architect - to a meeting. I was writing the architect with Robin Williams in mind. The boy witnesses a creative dispute the architect has with a colleague. I had called my friend, Joel, who knew something about architecture, to ask him what a controversial design element for an office building might be. He suggested a fountain in an atrium. A fountain may be a whimsical addition to an otherwise sterile office space. But the sound of falling water might also make people have to get up to pee a lot.

Perfect.

In the scene, the architect and his colleague argue in front of a client where Robin Williams would say, “Don’t tell me how to build a fountain in an atrium! I know how to build a fountain in an atrium!” Afterwards, he feels bad about losing his cool not only in front of the client but also in front of his mentee and advises him never to do what he did. There are more constructive ways to solve problems. This is a lesson the middle-schooler takes back to his own school project where he’s been having a dispute with someone on his project team. It was the only episode in the script where a student learns from a negative example.

Janice and Rosemary did not like this one bit. Janice contended that “Adults would never act like this. Adults would never speak this way to each other.” What she didn’t know was that I had lifted the dialogue verbatim from a court transcript printed in the L.A. Times of the O.J. Simpson murder trial, which was dominating the news at the time. It was a sidebar between the two legal teams where O.J.’s lead attorney, Johnnie Cochran, was arguing with the prosecution’s Christopher Darden in front of Judge Lance Ito[1]. At one point, one of the lawyers said to the other “Don’t tell me how to try a case in court! I know how to try a case in court!” I had just taken the phrase “Try a case in court’ and substituted “Build a fountain in an atrium.” I regretted to inform Janice that I wasn’t making it up. This is exactly how adults speak to each other.

Every scene I wrote was meant to reflect real life, borrowed either from my own experience, or found in something I read, or, as in the case of the skulls, something I was told. I explained to Janice and Rosemary that everything they were objecting to was precisely the reason I was brought onto the project. I was there to ground the academic message in recognizable human life with relatable characters. And that includes flaws and speed bumps and pancakes with maple syrup.

Eventually, they succumbed to that notion. They weren’t happy about it, but they understood. We had only gotten about thirty pages in before they finally surrendered and released me from Skywalker back to my natural habitat.

I turned in the draft and didn’t hear anything for a long time. Never a good sign. I remember getting an email from Steve Arnold about how he liked the skull story and would appreciate more of that kind of stuff. Nothing from George. After a while, Janice called. She wanted to know if I could add some scenes about an inner-city school. I said, “Why not make our school an inner-city school? After all, we’re in Utopia.”

I can’t say for sure, but what I believe happened behind the scenes was a conversation between George and his professional educators about how the educational community would respond to this utopian world we were building, about whether present day educators would roll their eyes at this vision – despite its best intentions – for being too detached from their ground-level reality.

I suspect Janice feared that backlash. And I also suspect she was right. The last time we spoke, I reminded her what they had taught me, that the techniques and technology they were promoting, although not widespread, were already being practiced in public schools around the country. They had sent me to some of those schools themselves. “Why don’t you do a documentary about where it’s actually being done?” I said, “Then, you won’t have to worry about your colleagues telling you this has nothing to do with real life.”

That was the last time I heard from Janice or anyone from the George Lucas Educational Foundation aside from the check, which to their credit landed in The Skro Zone mailbox with the alacrity of Din Djarin's N-1 Starfighter[2] and helped my family get through the first half of 1995. The script never got made. And although I spent those three misty Skywalker days with George Lucas, I never got to work with Zemeckis, Levinson, Spielberg, Hanks, or Goldberg…”

Instead… guess what? They made a twenty-minute documentary. Narrated by Robin Williams.[3]

It wouldn’t be the last time I talked myself out of a job.

But it all worked out. By June of ’95, after two years of wandering in the Tatooine desert[4], I landed my first sitcom writing gig since Seinfeld, which led to more or less steady work for the next twenty-five years.

Turns out, at the end of that rainbow over the Bay Bridge… there was a pot of gold.

As for the state of education now that 2025 has finally arrived, I’m no expert, but I’m not hearing good things. In 1995, we were four years away from the horror of Columbine. As I’m writing this, a notification popped up on my iPhone[5] about news of one more in what has become an epidemic of school shootings. This one at a Christian School in Wisconsin, each successive incident horrifying us less and less.

The Covid-19 pandemic showed that the “digital divide” Edutopia was trying to bridge in those early years is as wide as ever if not growing wider. Once the students were sent home, according to studies, more than half the students in lower-income families faced technology problems that prevented them from doing all their schoolwork.[6]

There are other problems as well.

I hear about the banning of books that deal with LGBTQIA+ issues and our heritage of racism. I heard about a program called “No Child Left Behind,” which was a businessman/politician’s idea of measuring student achievement through standardized testing, which, as my own mentor, Ralph Nader, argues only produces “standardized minds.” I hear of teachers not knowing if their student’s papers were written by them or by Chat GPT. I hear about parents suing schools for their kids’ low grades for using Chat GPT. I hear about teachers’ salaries not keeping up with the cost of living. I hear about teachers who already barely get paid a living salary using their own money to buy school supplies. I hear about the re-routing of public tax revenue from public schools to private schools in the form of school vouchers. I hear about administrator-heavy schools that have cut art and music programs to pay their salaries.

Ironically, as I was trying to help George Lucas promote the education of young people, the education of older, more powerful people came under attack. Back in 1995, one of the first things Newt Gingrich did in his short yet “scary” term as Speaker of the House was eliminate the Office of Technology Assessment, which since the early ‘70s had provided members of Congress with objective analysis of complex scientific and technological issues. No doubt this was an effort to discourage Congress from accessing authoritative information about health, safety, and environmental concerns, an early shot in the ongoing assault on expertise that gets in the way of Big Business and their political toadies from making money.

I know Edutopia is still fighting the good fight, providing substantial support and innovative ideas to teachers and students. I just wonder how George’s vision, especially of the technology, has adapted to the current circumstances. A recent peer-reviewed study by neuroscientists indicates kids learn better on paper than on screens. (Can’t help thinking of George with his stack of legal pads.) Yet, more and more schools are going digital, and big tech companies like Google are taking over the classroom, making billions of dollars selling Chromebooks. I know George and Janice’s dream of technology’s use in education was more interactive and egalitarian.

Unfortunately, education in the year 2025 sounds a lot more Grand Theft Auto than American Graffiti, a lot more Fury Road than Edutopia.

In rereading the script, I remembered that a final exchange between the seven-year-old character, Molly, and her mother (Abigail) had been inspired by a conversation I had had with my son, Sam, at around that same time. It was most likely influenced by my exposing him to the Star Wars universe after my trip to Skywalker. So rather than end this story on a dark, albeit realistic, note, I’ll take a cue from George about leaving one’s audience with a more positive vision. This is the last beat of the script I wrote thirty years ago:

MOLLY: Mom, next year for my birthday. Do I have to be eight?

ABIGAIL: You'll be eight, yes.

MOLLY: Do I have to?

ABIGAIL: Well, yes. That's the way it is. First, you're seven, then you're eight.

MOLLY: I don't want to be eight. I want to stay seven years old.

ABIGAIL: You mean like Peter Pan? You don't want to grow up?

MOLLY: No, not Peter Pan. I just want to be alive for a long time. Ms. Theodore said that in the future there could be flying cars and stuff like that.

ABIGAIL: I see. And you want to be around for it.

MOLLY: Yeah, I want to fly all by myself.

ABIGAIL: And you're afraid if you grow too fast, you'll miss all these great inventions.

MOLLY: Yeah. Maybe when I'm sixteen I'll stop growing.

ABIGAIL: Actually, your body will stop growing. But your brain never stops growing. You'll always be learning stuff.

MOLLY: Really?

ABIGAIL: I hope so... But you know what? Maybe you're on to something... Tell you what, Mol. No matter how many birthdays you have, you have my permission always to keep a part of your brain seven years old.

MOLLY: I can keep my brain seven years old?

ABIGAIL: Yeah, a part of it. I think that would be a good idea. What do you think?

MOLLY: (Smiling) Yeah!

FADE OUT:

THE END

[1] I always tell my lawyer friends that everything I know about the law I learned from the O.J. trial.

[2] Relax nerds, I don’t know this offhand. I had to look up the fastest ships in the Star Wars universe.

[3] I did get to work with Robin Williams ten years later on a completely different project. That’s a story for another time.

[4] Again, had to look it up.

[5] Known in 1995 as a PDA (Personal Digital Assistant)

[6] McClain, Colleen; Vogels, Emily A.; Perrin, Andrew; Sechopoulos, Stella; Rainie, Lee (2021-09-01). "The Internet and the Pandemic". Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Tech.

Any chance that George never read it, that Janice was a gatekeeper?

Well done!

Those notes made my blood boil. They reminded me of a story: A screenwriter friend was hired by Robert Redford to adapt a novel written by a native-American author. When he handed in his script, Redford said, "I love it, great script, but cut all the profanity." When the screenwriter asked why, Redford replied, "Indians don't swear." The writer, shocked, said, "But all that profanity is in the novel."