I slumped in the passenger seat staring out the window at the silhouettes of palm-trees smudged against the night sky as Shelley drove me to my bereavement flight.

The call had come a couple hours earlier that Wednesday evening. I had been sitting at our round glass dining room table having a casual conversation with Shelley’s mom and dad, Henry and Dana, who were visiting from the East Coast when the phone rang. It was my younger brother, John. Someone at the hospital had called him. Dad had gone into cardiac arrest while in Intensive Care recovering from a routine hernia operation. It had taken them twenty minutes to get his heart beating again. Twenty minutes? He couldn’t still be alive, could he? I mean really alive? After twenty minutes?

That’s what I asked my father-in-law, who was a doctor. He gave me one of those subtle, sympathetic headshakes TV doctors use to let next of kin know the patient isn’t going to make it.

As I watched the Los Angeles cityscape float by on the way to the airport, I tried to come to terms with the fact that my father was gone.

“Damn,” I thought, “I wasn’t done raising him yet.”

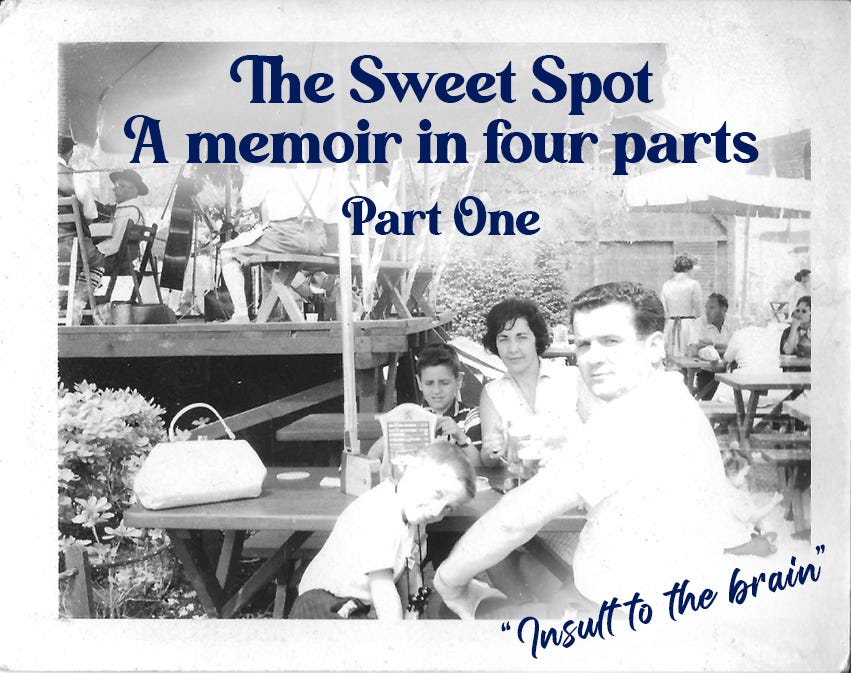

Our father, Clarence Skrovan, was born in Cleveland, Ohio, on the fifth day of 1930, about ten weeks after the stock market crash that led to the Great Depression. He was the second of six kids, four boys and two girls. They were poor. His father, Grandpa Skrovan, had an eighth-grade education and worked in a foundry. Dad didn’t quite qualify for membership in what they tell us is The Greatest Generation, those born between 1901 and 1926. His was The Silent Generation, born between 1927 and 1945, the generation who struggled as children during the Depression and World War II.

From Cleveland Hopkins Airport, it’s an hour drive east to my hometown, Chardon, Ohio. I got to Geauga Hospital on Route 44 just a few miles from where I grew up at about six Thursday morning. John had driven up from Ithaca, New York, and had arrived about a half hour before me.

Dad was in the ICU, unconscious, eyes closed, his head involuntarily twitching, as if water were dripping onto his electrical circuits. They had adjusted his bed so he was sitting relatively upright. The tube down his throat was connected to a respirator to help him breathe.

I was amazed he was alive at all. The hernia operation itself had gone smoothly, but the next day his blood pressure dropped enough to move him to the ICU. They had pushed it back up, but in the middle of the night it dropped again, this time off a cliff. Seconds after the alarm bells went off, the staff rushed in and worked to revive him, able to keep enough oxygen flowing to his brain for the twenty minutes it took to jump start his heart. If he had been anywhere else, he would have been a goner. Turns out the ICU is the ideal place to have a heart attack.

As a child, Dad had suffered a serious bout of scarlet fever, which has been associated with heart damage. This was before antibiotics had rendered the disease relatively harmless. He also had had an emergency appendectomy as a child, a procedure his parents were always quick to remind him cost $200, a significant sum back then, which had set the family back for years. This sense of guilt his parents put on Dad was one of the reasons he and Mom never discussed money with me or John when we were kids. They didn’t want to pass on that burden to us. Whenever we asked, they told us it was none of our concern.

Through those difficult years, Dad developed a sturdy work ethic. He and his older brother Dan worked odd jobs throughout their childhood, delivering newspapers, ushering at movie theaters, shoveling snow. Even before his teens, Dad worked every day after school, handing over most of his meager earnings to his parents to help support the household. His report cards were filled with Ds and Cs because all these jobs left him little time for schoolwork.

Because he was tall for his age and had suffered severe acne, which gave his face a more weathered look, people always thought Dad was older than he was. He told stories about how as a fifteen-year-old during World War II, he’d get suspicious looks from uniformed moviegoers at the downtown theater where he ushered. “Why aren’t you in the service?”

Eventually, he did serve in the Navy during the Korean War, although he never made it to Korea. He was deployed on a communications ship that steamed up and down the East Coast and around the Caribbean, never engaging in hostilities. Dad always joked that the only combat he saw was in Boston bars, which he referred to as “The Battle of Scully Square.”

Although they grew up poor, both my parents came of age post-World War II, a time of unprecedented national prosperity, when America sat on top of the rest of the world, which at that time was a smoking ruin. The economy boomed and the middle class swelled. Dad went to night school to study business, not long enough to get any kind of degree, but in those days, it didn’t matter, especially if you had the good fortune to be white. Natural people skills and a quick wit carried Dad a long way. He worked in sales for a number of small companies in the Cleveland area, but he dreamed of one day owning his own business.

I, on the other hand, was born in 1957, the sweet spot, the absolute peak of the Baby Boom. More importantly, it was the second half of the Baby Boom[1]. I turned eighteen in 1975, about six weeks before the fall of Saigon. My draft registration was returned. That’s why I call it The Sweet Spot. Too young for Vietnam. Too old for any of those other misguided wars that came later.

Dad and I had both just missed our wars.

But this is where Dad and I parted ways politically. He didn’t like the government interfering in economics. I didn’t like the government sending us to war. It was the classic generation gap issue of the time. His thinking was greatly influenced by the “just war” that was World War II, mine soured by the colonial war that was Vietnam. We mixed it up over politics at the dinner table, much to my mother’s dismay.

Dad had been battling congestive heart failure for a number of years. Earlier that year (2009), doctors had discovered that his pacemaker’s battery had died and likely had been out for months, sending him into bouts of A-fib—irregular heart beats. Shock treatments and heavy toxic medications had only managed to treat the condition temporarily. It always came back.

By Friday, Dad’s head had stopped twitching, and he opened his eyes. He seemed to recognize me and John but couldn’t speak with the tube down his throat. They had run a brain scan. Amazingly, his scan, the neurologist told us, was clean. As far as the test went, he had passed. She showed us the schematic and told us that his scan wouldn’t look any different from ours. That didn’t tell the whole story, however. He still had had what she called an “insult” to the brain, a trauma that modern technology could not yet completely nor reliably measure. We would know more as he continued to wake up.

“Insult to the brain,” she said. Not “a blow to the brain” or “a punch to the brain.” His brain had merely been insulted, as if Don Rickles had called him a hockey puck.

Dad had bought a joke book to prepare for his duty emceeing the St. Mary’s Church “Gay 90’s!” themed fundraiser/talent show. The book was 2001 Insults For All Occasions. Looking back now, it seems an odd choice as prep for a church talent show. Was he loading up in case he got heckled? Was he looking for lines to comment on the acts? I’m not sure, but I have a vivid memory at ten years old or so going through the book with him. When he set it aside, I would pore through it, trying to memorize some of the lines like these:

“You’ve got a good head on your shoulders. Too bad it isn’t on your neck.”

“When they were passing out brains you thought they said trains, and you missed yours.”

“Why don’t you take a long walk off a short pier.”

After the show, which was a big success, my parents had invited my aunts, uncles, and grandparents for an after-party at our house. While everyone congratulated my dad for the great job he had done, I kept popping in, trying to grab attention by spouting the insults I had memorized from the book.

“Yeah, he did a great job. He drew a line around the block. Then the police caught up with him and took his chalk away.”

No one seemed to take much note, but I must have been obnoxious enough, because at one point Grandpa Skrovan took me aside and sat me on his lap. He taught me a Slovak word from the old country: drzý,[2] equivalent to “wise guy” or “smartass.” He gently advised me to stop being that. “Don’t be a drzý.”

Dad’s primary care physician had come by to check on him. She was the doctor who knew him best. She had seen the results of the data from his cardiac arrest and pointed out that in the final analysis, it was technically not a cardiac arrest. Something about the enzyme readings told them that it had actually been a pulmonary arrest. It was his lungs - not his heart - that had stopped working.

This was not surprising. He had been suffering from congestive heart failure for years. Essentially, his heart was not pumping vigorously enough to keep his lungs from filling with fluid, a condition exacerbated by the A-fib. Sometimes, if he leaned back too far in his easy chair, he’d feel like he was drowning.

In fact, only about six months before this I had accompanied my parents to a medical facility where they had tried yet another unsuccessful A-fib procedure on Dad. Before Dad was led out of the office, a young doctor took Mom and me aside and recommended that we not put him through that again. Apparently, the chemicals used at that time to treat A-fib were extremely toxic. This doctor told us that if it were him, he wouldn’t want these injected into his body no matter what the circumstances.

The pulmonary arrest was good news only in the sense that Dad’s heart wasn’t any more damaged than it already was. The specialist told us he thought Dad could recover. It would be a matter of weaning him off the respirator. They wouldn’t pull out the tube right away because re-intubating him was a painful skirmish. They would just turn off the ventilator for fifteen minutes, a half hour, forty-five minutes at a time to see how long he could maintain sufficient blood oxygen levels breathing on his own. It looked like the old man was going to make it after all, living up to one of his favorite lines “We Skrovans, we’re hard to kill.”

End of Part One

Tomorrow: Part Two - Therapeutic Fibbing

[1] This cohort has also been labeled “Generation Jones,” a term that alludes, perhaps, to the disadvantages of being born in a subset of the Baby Boom and trying to “keep up with the Joneses (our older siblings?)”. Or maybe we were “jonesing” for something out of reach. Neither described my experience. I believe we had all the advantages. I’d call us “The Luckiest Generation.”

[2] Pronounced “driz-EE”

Thank you for sharing this… a universal experience in so many ways.

You hadn’t finished raising him 👏🏽 👏🏽