I always try to get there about a half hour early so I can jog out to the outfield to do my yoga poses: chair, half moon, bow pull. Every once in a while, I’ll mix in a sun salutation. I don’t care how douchey it looks. Even when I take an actual yoga class, I’m like that broken piece of lawn furniture you can’t quite bend back into shape. You’ve got to stick a wedge under my leg to keep me from tipping over. But now I’m at the age where I’m over feeling self-conscious about it.

I do it because I’ve seen too many of these younger guys hit a ball in the gap, churn around second base digging their way to third, and then throw up their hands and collapse to their knees as if they’ve been shot in the back like Willem Dafoe in “Platoon;” or they do the stumble, roll, and face plant like Jim Brown in “The Dirty Dozen.” It’s a disturbing sight, a guy writhing on the ground, his mouth contorted into a rictus of pain and disbelief. He can’t believe his body has betrayed him, stabbed him in the back of the leg. This, of course, doesn’t stop the rest of us from standing over him and, after the obligatory show of concern, chuckling about whether, like a fallen racehorse, we should put him out of his misery.

I’m warming up to play in my regular 8:30 am Saturday fast-pitch softball game, although “fast-pitch” is a bit of a misnomer. We’re not talking about guys windmilling the ball in at sixty, seventy miles an hour. Windmilling is against the rules. It’s called “modified fast pitch,” meaning it’s more “flat pitch.” I explain that because I need you to know that this is not a casual beer league game. It’s competitive. You’ve got to bring some skillz.

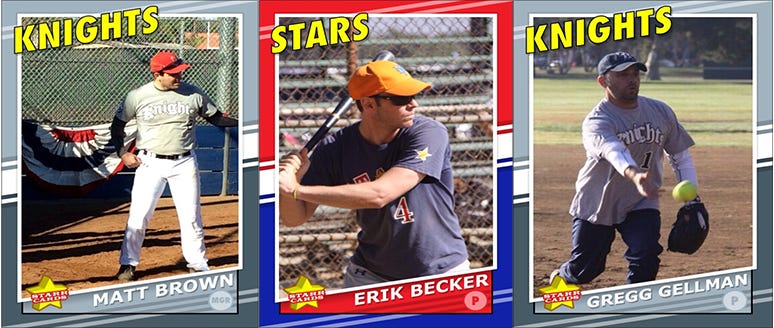

It’s not even really a league per se. It’s a collection of twenty-five or so guys who get together and divide up into two teams. One team wears blue shirts with the word “Stars” emblazoned in red across the front; the other team wears white shirts with the word “Knights” in white letters with black and gold trim. We play a nine-game series, and whichever team is the first to win five games wins the series. We take a picture of the winning team in front of the backstop; then we divide up the teams again, trade shirts, and embark on another nine-game “series” the following Saturday.

Players range in age from twenty-five to Jeff, who turned seventy-nine this year. I remember Jeff’s sixty-ninth birthday. That year, we stopped the game and sang “Happy Birthday.” Not only did he enjoy it, but so did his ninety-five-year-old mother, who was sitting in the stands still watching her boy play ball. Jeff plays second base and is trim (trim – let that be a lesson to us all) with a gorgeous head of thick gray hair. Never wears a hat. Not with that hair.

I’m not the oldest guy in the league, but I am one of the few we call “The Monument Men.” Anyone over sixty qualifies. My early arrival and yoga routine is all a part of my unabashed injury prevention program. My theory is the guys who tend to get injured are those between thirty-five and fifty. These are the guys whose brains have not yet adjusted to the limitations of their bodies. They still think they can roll out of bed five minutes before game time and sprint down to first base without having their hamstring snap and curl up the back of their leg like a broken piano wire.

Starting in my mid-thirties into my early forties I played in what was called The Show Biz League out here in L.A. This was a real league with about ten or so teams. By the time I started playing, it didn’t have much to do with show biz except that Tony Danza of “Taxi” and “Who’s the Boss” captained a team. I got recruited by a fellow comic named Jon Ross to play for a team called “Bernie’s Ballbusters.” Another comic, Bernie McGrenahan, sponsored that team.

You might as well have called it “The Ringers League.” This was some serious softball. Fast pitch. Bunting. Stealing. A lot of guys had played college ball, some even made it to the College World Series. A guy on Danza’s team was signed as a replacement player during the Major League strike of 1994-95. Jesus, could he hit the ball a long way. Unlike my home state of Ohio, California is a hotbed of baseball talent, simply because the weather allows you to play the game all year round. In Northeast Ohio, we could play only from April until August, and that was provided the snow had melted and the fields had dried out by the start of the season. We always had at least one game snowed out. By the end of August, we were already onto football.

I had always been a jock growing up, starting with Little League baseball at age eight and CYO basketball from the fifth grade. My best sport was football, which I played for ten years from seventh grade all the way through a decent college career as a defensive back at Yale in the late seventies. All through that, aside from assorted bumps and bruises, a bunch of contact lenses popping out of my eyes, and a couple of sprained ankles, I had managed to stay relatively injury free.

In my early forties, I noticed a hitch in my right leg. I had to stop playing pick-up basketball because I could no longer move laterally well enough to guard anyone. And though in softball, I could still dive for a ball in the outfield, getting my legs back under me took about a half hour. Eventually, I had trouble tying my shoes. In order to reach something from the bottom shelf at the grocery, I had to stick my right leg straight out behind me after looking both ways lest I get t-boned by a passing shopping cart.

Eventually, Shelley convinced me to go to an orthopedist who showed me an X-ray of my right leg and pointed out I had very little cartilage left in the hip joint.

I said, “So this is probably from all the high-impact sports I’ve played, right?”

The doctor said, “Nope. Looks like you were born that way.”

“Born that way?”

“Yep. You have shallow sockets.”

Shallow sockets? That’s an odd thing to find out about yourself. It didn’t feel like me. Shallow sockets? I never thought I’d be the one picked out of that lineup.

“Yes, that’s one, officer. The one with shallow sockets. I’m sure of it.”

So now all of a sudden, I’m a man with shallow sockets. All this time I had this – it certainly doesn’t rise to the level of birth defect – but this genetic flaw. Obviously, it’s not like the doctor had diagnosed me with cancer, thank God, or a genetically defective heart valve, or that I just found out I was adopted, but still, shallow sockets? Really? Me?

I shrugged and turned to Shelley, “Well, I guess I’ve had a good run.”

I was going to need a hip replacement, but not then. I was too young. At that time, they didn’t like to do them for people under fifty-five, because the materials wore out and there are only so many times you can drill into the bone. That left me with the prospect of a ten-year limp.

That sentence was commuted after about seven years due to advances in both material and a new technique in hip replacement called the anterior approach. That means they go through the front instead of the back (posterior) or side (lateral). Going through the front means they don’t have to cut soft tissue, which makes for a much shorter recovery time.

I’ve had a lifetime essentially free of major injury or health problems. And even this was the lesser of potential evils. Hips are pretty simple joints, a ball, a socket; you saw off the bad bone, pound a metal rod into the good, and you’re done. It’s high-tech carpentry. Knees and shoulders are much more complicated since they are full of ligaments and tendons and menisci, things that twist and tear.

I’ve always been fortunate that way. I’d say it’s 99% luck and 1% knowing how to fall down. It’s not fair. It’s terribly unfair. I’ve always been lucky. Sometimes I think if I ever did get cancer, it would be the best cancer, the kind that actually extends your life and makes your hair grow thicker.

I had been sidelined for about seven years of my middle-aged prime until about a year or so after the operation, I got a call from Bob, an old buddy of mine from the Show Biz League. He asked me if I wanted to play in this fast-pitch game on Saturday. They called themselves the WSL, the West Side League because they played at various fields on the West Side of Los Angeles. They were looking for subs because some of the regular guys couldn’t make it. I wasn’t so sure I was ready for that. I wasn’t sure I wanted to play again at all. My right leg was still much weaker than my left. I hadn’t done anything close to a sprint in years.

But the jones was still there. I had been playing ball since I was eight years old. There was nowhere I felt more comfortable than on a baseball field, not a nightclub stage, not a TV set. There was no other place I knew exactly what to do, knew what my role was, and knew how to act than on a baseball field. So, I showed up. I started subbing every week, playing one week for the Stars, then the next week for the Knights until eventually the commissioner of the “league,” Michael Katz invited me to become a regular.

When I first started playing with this group, there were a lot of arguments. Guys took this shit seriously. There was an edge to the proceedings, a lot of smack talk and not the friendly kind. Not everyone liked each other. Complaints about the umpire’s calls boiled over into Billy Martin/Earl Weaver-level tantrums.

We had a pitcher named Tony (not Danza), a regular on a TV series at the time, who off the field was a genuinely sweet guy, but apparently was also a recovering alcoholic, who sometimes raged at our umpire, Karl, like that kid on YouTube whose parents took his video games away.[*] (My favorite part of that video is when the kid rage-strips down to his underwear and finds himself holding a game player in his hand. And in an indication that his anger at his parents has now turned inward, he tries to stick the game player up his own ass.) Tony had a lot of moves in his repertoire, stomping and screaming, fence kicking and slamming the dugout gate over and over again. I would have handed him a bat to stick up his ass if I hadn’t been afraid he’d crack me over the head with it first.

When Tony first went off, it was a little disturbing, but as it went on and on—and on--it got funny to watch in the way it’s funny to watch a kid in a grocery store meltdown when it’s not your kid. But when it was over, it was over, and after the game, there was Tony in his truck giving Karl a ride home as if nothing had happened.

It wasn’t long before I was addicted to playing in this game. We started at eight-thirty in the morning and were done by ten-thirty, eleven, getting out from under that relentless Southern California sun before it could fry us like bugs under a magnifying glass. These games turned out to be tremendously therapeutic, both emotionally and physically. Emotionally, it was simple: I was playin’ ball. Physically, it motivated me to go to the gym during the week, not only to build up my surgically repaired right leg but also to stay in good enough shape so when I came home late Saturday morning, I would still be able to move the rest of the weekend.

It became important for me to maintain my strength. I had always considered myself a power hitter. Now, in my advanced years, I could literally measure myself against the younger guys by how far I could hit the ball. Suffice to say, today I’m a singles hitter. After the long layoff before my hip replacement, I could tell my reflexes had deteriorated. I was playing third base in one of my first games back. Someone hit a screaming line drive that went right through my legs, just nicking my penis. This wasn’t a short hop. The ball never touched the ground. My mitt was right in front of me, inches away. I just couldn’t react fast enough. From behind, it must have looked like the softball rocketed out of my ass. I wasn’t wearing a cup, but fortunately, it didn’t “square me up.” It didn’t hurt. It was more like a warning shot, telling me, “Get to the outfield, old man.”

So much of reaction time and hand-eye coordination is anticipation, guessing where the ball is going to be, and moving your hands to that spot before it gets there. And that takes practice. When you’ve been away for a while, it takes a few repetitions to regain the confidence you need to protect your nuts. And the key is to do it enough to where you stop thinking about your nuts. In some ways, I guess that’s what really separates the professionals from the amateurs, the degree to which you are thinking about your nuts. And I’m using nuts as a catchall for other parts of the body: nose, mouth, eyes, fingers, vagina, all of those particularly vulnerable areas, although I should probably leave the vagina talk to those who actually have one. I’m just assuming. My point is: professionals never think about their nuts. I, as an experienced amateur, only occasionally think about my nuts. I suppose I could wear a cup, but that seems like too much trouble and as a Little Leaguer, I remember a lot of chafing.

My reflexes improved the more I played, although I did decide never to wear sunglasses on the field. At my age, I needed as much light as possible streaming into my corneas.

To protect my nuts.

Over the years, the game has mellowed. Katz weeded out the crankier players. Tantrums would no longer be tolerated. He hired a great umpire, Joe, who started with us as a player but was also a trained umpire. He ran the games with authority and was very rarely questioned. He was like the dad who made us all behave. Once he accomplished that, which took about eight years, he started playing again. The whole enterprise became more collegial without losing its competitiveness. It’s amazing how you can construct some artificial goal like winning an essentially meaningless nine-game series and have people sliding, diving, and cursing as if it’s the most important thing in the world. We’ve been athletes our whole lives. It’s in our blood.

Surprisingly, I know relatively little about the guys I play with. We very rarely talk about work, or what we do, or even our families. It’s mostly about the ball. Inevitably, you pick up some details, though. Doug is in real estate. Gellman is an entertainment lawyer. Rollie sells insurance. Chuck is an actor. Erik is a high school principal. Barry is a writer. Katz has a successful women’s shoe business.

What I do know intimately about them is how they play the game. I know that Rich takes no time between pitches, so be ready to hit when you get into the box. Chuck has all these fancy dipsy doodle wind-ups to try to throw off your timing. I know that Pedro is great at catching ground balls to either side, but when it’s hit right at him, better back him up from the outfield. Post is a solid fielder you can put anywhere on the infield. Jeep and Andrew usually hit into the gaps. Jesse has an uncanny ability to draw walks, ducking under the ball, and a willingness to make the pitcher throw two strikes before he swings. Zach is super-fast. Better get rid of the ball quickly. Never take your eyes off of Ryan when you’re coaching third. He’s a dead pull hitter who will take your head off with a line drive. Reza, a lefty pull hitter, will occasionally dink a ball the opposite way. Monument Man Tom has occasional pop to left and will burn you if you cheat in too much. Chris has got power to all fields. Matt, Doug, Dave, and Dennis have rocket launchers for arms. Don’t try to take the extra base on them and when you do get a hit, run hard to first or they will try to throw you out from the outfield. Dylan hits line drives to the opposite field. David, Sam, and Alec have tremendous power. Better make them hit your pitch out of the strike zone, or you can kiss that ball goodbye. And sometimes even that doesn’t work. Pitchers know I will very rarely take a strike. I’m up there hacking at the first thing that looks good. We all have the book on each other. Our profiles have been downloaded and stored. We don’t need a spray chart to know where to play each other.

The younger guys tend to be unmarried or childless. The older ones have kids who are at least teenagers at that stage of life where having Dad around is not only not that important but actually an annoyance. Very few of the guys have babies or toddlers. Having kids that young makes it hard to get away on a Saturday morning. Babies have knocked more guys out of the game than injury and old age. When someone’s wife gets pregnant for the first time, the countdown begins. Some will foolishly insist that having a child won’t keep them from playing. He’s worked it out with the wife, he claims. The married veterans smile indulgently, knowing we’re talking to a ghost. His image is fading. Best you can hope for is that he’ll materialize once in a while as a sub when his wife takes the kid(s) to visit her parents. When the child is about to arrive, we’ll congratulate him, shake his hand, pat him on the back, and then watch him shuffle into the parking lot and toss his hat, his mitt, and his cleats into the trunk, equipment soon to be replaced by a diaper bag and a stroller. We lost Daryl that way, one of our better players: third baseman, mid-thirties, strong arm, tremendous power, loved the game. Daryl had his first child and actually made it back to play semi-regularly. It looked like he was going to be the exception. But then it happened again. He re-impregnated his wife. This time it was too much. He couldn’t recover. Having a kid in this league is not unlike having Tommy John surgery, but instead of being out for eighteen months, you’re out for eighteen years.

Since I’ve been playing, Katz has been able to book us at about a dozen different public and private fields in West LA. Like some sort of itinerant, barnstorming enterprise, we move from field to field, depending on the season and whether some other officially sanctioned league (Little League, high school, public park) has priority. And like a jewelry store at the mall, the diamonds vary tremendously in quality.

But as I have gotten older, I find that the condition of the playing field is no longer the first thing I take into account. These days, I am less concerned about whether the rocky infield undulates like the North Sea or the outfield is a condominium complex for gophers. Today, the first thing I look for is the placement of the nearest men’s room. And when I say “men’s room” that could also mean Port-o-Potty, that historic monument that marks the tenuous link between civilized society and a bear shitting in the woods. Or more importantly, me shitting in the woods.

Whatever the nature of the facility, I have to calculate the distance between it and my position in the field like a sabermetrician calculates a Wins Against Replacement formula. If I have to go -- and I promise you, I will – and say I’m up fifth in the inning, how long will it take me to make it to the bathroom, which I reckon is approximately fifty-five yards away, so I can get back in time to take a couple of swings in the on-deck circle before it’s my turn to bat? Or how likely is it, given which part of the lineup is due in our half of the inning that we go quickly one-two-three, and I can’t make it back in time to take my position in the field?

Let’s see, Pedro’s up this inning. I know he’s going to swing at the first pitch no matter where it is, which means I can’t afford to walk to the men’s room. I’m going to have to get a good jump on the third out and at least jog while maintaining good route efficiency, routes that I have scouted before the game on the lookout for gates that may appear open but are actually padlocked with a long chain. Our dugout this week is on the first base side, so I won’t have time to drop off my mitt on the bench. I’ll have to carry it with me. I’m wearing bike shorts underneath my baseball pants, which will take me a few extra seconds to free the equipment. So I’ll sprint there, pee fast, no more than three shakes, which is about two under the current minimum, then come out and assess the game situation. If we’ve got men on base, maybe then I can walk briskly back and catch my breath before I step into the batter’s box.

Baseball has never been a simple game.

Lately, we’ve been playing at a beautifully manicured girls’ softball field at a high school in Culver City. It has a fence and a level outfield, where you don’t have to worry about stepping onto a metal drainage grate going after a fly ball. We moved the plate back about fifteen feet and use wood bats so as not to turn the game into Home Run Derby. There is usually a lot of other activity on the adjoining fields on Saturday morning. School age-kids playing football, lacrosse, running track. On occasion, I’ll catch a glimpse of a middle-aged dad in cargo shorts, who has turned away from his daughter’s noisy soccer game. He leans against the fence with his hands entwined in the chain link watching us, wistful, waiting for his kids to grow up.

Only occasionally has anyone ever watched us play, a friend of Jeff’s, Rollie’s daughter, Lisbe’s son, Charlie, when he was little. They stop by every once in a while. Otherwise, the stands are empty. No roar of the crowd. No words of encouragement: “Come on, honey! You can do it!”

A few years into the league, I noticed a woman coming regularly to watch Mark play. I asked him who she was.

He said, “My girlfriend.”

I said, “You just started going out, didn’t you.”

He said, “Yeah. How did you know?”

“Because she’s here.”

I’m glad I can still play the outfield. I’m trying to put off playing first base as long as I can. First base is the Florida of softball. It’s where all the old people end up. As you get older and more infirm, you start migrating, slowly, inexorably, to the right side of the field. The shortstop who could backhand a shot deep in the hole or the third baseman who could fire the ball across the diamond like a human T-shirt cannon moves to second or first base. The center fielder, who could track down any ball hit over his head, or the sure-handed left fielder, who could make a sliding catch in foul territory moves to right. First base is the last lily pad before they nudge you completely off the field and into the dugout where you sit alone like a rescue in a kennel peering at the other dogs off their leashes gamboling in the park. At best, you’re a DH. And you better still be able to hit to justify that.

A few years before I became a Monument Man, I was playing for the Knights. It was the bottom of the ninth inning. We were losing by nine runs. I had made the last out of the previous inning, so when we got back to bat, I jogged over to coach third base. We made two quick outs to start the inning. The game was all but over. The last of our guys came up. His name was Edan. A friend of Carmine’s, he’d been subbing for one of the regulars this series. Edan hit an easy chopper to the third baseman, Els, who fielded it waist high, a nice, easy hop. Game over, except Els proceeded to sail the ball over the first baseman’s head. So the game was not quite over. Edan was on first, and our next batter got a base hit. Edan rounded second base and headed for third. Now, if it had been me, I probably would have stopped at second. Because at that time I was fifty-six and the Arch-Angel Discretion always reminded me to go station to station. But Edan was thirty-one. He was barreling to third. And it looked like he was going to make it pretty easily. So I raised my hands above my head, which is the baseball sign to “stay up.” No need to slide. I wouldn’t have slid, not at my age. However, Edan was thirty-one. He was going to slide. So he slid into third base, and I notice his ankle turned slightly as his foot hit the dirt. It didn’t look too serious, but Edan screamed as if he’d been knifed. Turned out it didn’t take much to give him a compound fracture of the ankle, which was what the doctors later diagnosed at the hospital.

But we didn’t know that then. At this point, Edan is merely writhing on the ground while a bunch of Knights and Stars stand over him, trying to figure out what to do. In retrospect, we probably should have simply put something under his head and let him lie there. It was not as if he were in a swimming pool and was going to drown. It was just dirt. Mother Earth. Solid ground. But we’re guys. We couldn’t just let him lie there. We had to “do” something. So a couple of us lifted him up underneath the arms and carried him to the bench, his foot dangling at the end of his ankle. Every movement was agony for him. We carried him over to the third base bench and rested his injured leg on my lap. Chuck supported his back. We were trying to keep him very still because every little breeze on his shattered ankle caused him to go “Arrrgggghh.” We made no jokes about euthanizing him like a horse. This was too disconcerting. Instead, Katz called 911. He told them, “It’s not life and death, but we’ve got a guy here in a lot of pain.”

Meanwhile, Edan yelled, “Carmine! Carmine! Don’t call my wife! Don’t tell her yet! Arrrrrggh!” And what I found out was that Edan’s wife was about three days from having their first baby, and he didn’t want to upset her. At least not until he was in the hospital and no longer going “Arrrgghhh!”

A few minutes went by as we waited for the ambulance, and finally one of the guys, probably Katz said, “Well, we might as well finish the game.”

Come on, what were we going to do, stand around and chant over him? Or God forbid be empathetic and supportive? What are we, the Fab Five from Queer Eye? No, we were going to finish the game. We got a pinch runner for Edan, and the Stars retook the field. Our next batter got a hit. Edan’s pinch-runner scored.

I tried to cheer him up. “Hey Edan, you scored!”

Edan: “Owwwwwwwgh…”

That was better. Owwwwwwwgh… was better than Arrrgghhh! At least in my medical opinion.

Then the next guy got a hit. Another run. And then another hit and another run, and all of sudden, we had a ninth-inning two-out rally going. We were coming back, baby!

Through all of this, by simply remaining absolutely motionless, Chuck and I managed to keep poor Edan still enough that not only had he moved from “Arrrgghh!” to “Owwwwwwwgh” he had stabilized to “Oooooh, Oooooh, Oooooh.” We had taken him from Code Red to Code Yellow, from screaming all the way down to a perfectly manageable whimper.

And the rally continued. Game ain’t over ‘til it’s over. We got another hit. And another run. We were down by four now. We could actually pull this out. We were within striking distance. It was at this point I realized that my spot in the order was coming up. If someone before me didn’t make that third out, I had a moral dilemma on my hands.

The next guy got a hit. Another run. And sure enough, I heard, “Skro, you’re on deck!”

No sign of the ambulance. I looked at Edan, his face a mask of anguish. If I didn’t bat, it would be an automatic out. Rally snuffed. We’d lose. If I moved, Edan would start screaming again. I so much wanted the next batter to pop up for the final out. Although, there was still a part of me that thought what a victory this would be if we came all the way back. It wasn’t for the series title, but… still. The next batter walked. I looked at Edan, then back at the field. Then back at Edan, then back at the field.

Then, “Skro, you’re up!”

I had to make a decision.

I took a deep breath and said… “Chuck, get over here and take his leg.”

Edan’s eyes widened in silent horror. I said, “Edan, dude. I know this is going to hurt. But you have to understand. You’re thirty-one. You’re about to have your first child. You’ve got your whole life ahead of you. I’m fifty-six. I’ve only got so many at-bats left.”

I did, however, resist the urge to tell him the sad, sad story of the poor little boy born with shallow sockets.

Edan closed his eyes and nodded almost imperceptibly. If memory serves. Suffice to say, that was how I chose to interpret it.

I started ever so carefully to slide my body out from under his leg, patiently, inch by inch, like a cat burglar trying to limbo under a security beam. But it didn’t matter how gently I moved. Edan ratcheted back up to “Owwwwwwwgh…” Not quite back to Code Red. He was in Code Orange. I’m not a monster.

Finally, I stepped into the batter’s box and suddenly realized how much worse I was going to feel if I didn’t get a hit. I couldn’t have put Edan through all of that torment and make the last out. How could I look him in the eye after that?

Don’t worry. I got the hit. Sharp line drive to center field. We were now two runs down.

Then the next guy swings at the first pitch. Pops out. Game over. We lost.

Edan never came back to play with us after that, but Carmine assured me that Edan was up and around and enjoying his baby. Ankle or no ankle, we knew after the baby’s arrival Edan was a goner. I hope to see him again one day and thank him for enduring all of that pain to save my last ups. If I’m around long enough, maybe I’ll find him gazing through the metal fence, hands gripping the mesh above his head, bouncing up and down on his toes just enough to make his ankle click, and thinking, “Soon. Soon.”

Coda: I said we were down nine runs in the bottom of the ninth. I said that so as not to confuse you. It was actually the bottom of the tenth. We always play ten-inning games. Why? Because we’re a bunch of guys who want to spend one more inning playing in the sun on a Saturday morning.

Fun read Skro, brought back a lot of good memories (and some forgettable ones).

This one made my hamstring hurt. I totally enjoyed the read. Thank you!